Tucson, USA

Written by Gary Paul Nabhan, Colin Khoury and Douglas Gayeton

Photography and video by Douglas Gayeton

Research by Gabi Freckmann and Maggie Helmke

TUCSON, USA — THE TEPARY BEAN, a nutritious legume that’s high in protein and rich in antioxidants, is native to the Sonoran Desert, where it thrives in extreme climatic conditions. The tepary is also one of twenty-five crops selected by the Reawakened Initiative both for its health benefits—the bean’s high fiber content provides excellent benefits for those with diabetes, because it causes a slower release of its sugars—as well as its resilience in the face of climate change.

People have been growing agave, maize, and squash in the Sonoran Desert for nearly 4000 years—as long as anywhere in North America—but can a hard-baked sandy landscape dotted by cacti, mesquite trees, and low rock outcroppings, a place with little rain and high temperatures, contain the keys to help nourish us as we grow to be more than 10 billion?

Like most other things around these desert borderlands, finding the answer requires resourcefulness, patience, and the know-how to identify these lands’ subtle gifts; they’re hidden in rocky crevices and dry washes, in cracks in pavement, and under scraggly trees. They hold secrets that may prove vital in a time of increasing climate uncertainty.

Written by Gary Paul Nabhan and Colin Khoury

Photography and video by Douglas Gayeton

TUMACACORI HIGHLANDS, NORTH OF THE ARIZONA/SONORA BORDER—

This landscape of thorny agaves, cacti, mesquite trees and rock is not the first place one might imagine searching for the future of food. How can such a hot, dry place contain some of the keys to nourishing the world?

We’re in the desert, an hour south of Tucson, in southern Arizona. Giant, natural walls of stone rise hundreds of feet above our heads to form a big horseshoe-shaped canyon appropriately named Rock Corral. The heat here can be punishing, and the rain scarce, and that was precisely the point. For the area is home to precious wild plants tolerant of such stresses, hiding in crevices and under scraggly trees providing just enough shelter for their survival.

This is one of a handful of places in the US where wild chile peppers grow. They’re the ancestors of the planet’s most important condiment, the spice that provides nutrients, flavor, and pain-induced endorphins to cultures worldwide. This “crop wild relative” – known around here as chiltepin (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) – occurs from right here in Arizona, all the way south to Brazil. We notice prehistoric potsherds and grindstones at our feet. Archeological and linguistic evidence suggests human use of species as far back as 6000 years ago, in what is now Oaxaca and Puebla, Mexico, where the plant was probably domesticated.

The hodgepodge of land managers, agricultural scientists, conservationists, and educators visiting the canyon with us want to see the wild relative growing in its natural habitat. We head downhill to one of the main washes that drains the area. There, on alluvial shelves, hidden under thorny trees, we find wild chiles. Compared to their domesticated kin, the plants are small and scruffy, especially at this time of year. They have just a few leaves and pea-sized fruits, awaiting the return of the rains to start growing again.

Wild chiles remain important to local people, and some families have made foraging trips into this canyon to pick peppers for centuries. They are prized in these desert borderlands for their flavor, but more than anything for their heat. Families often keep a small mortar and pestle on the dinner table to grind a bit of fresh chiltepin to season their meals. On the other side of the border in Sonora, Mexico, foragers make a living collecting, sun-drying, and selling over 50 tons of the peppers a year. They sell for as much as $100 a pound.

While the plant is important in the region, what can it contribute to the future of food around the world?

The answer is resilience. The plants that call this canyon home—which also include the genetic relatives of sweet potatoes, cotton, grapes, tepary beans, and 50 other wild relatives—need nothing from humans to survive. They have to grow both when there is enough water and when droughts hit. Wild plants’ leaves angle to catch just enough sunlight without losing too much moisture; their flowers bloom at night to attract bats, birds, and moths that are active during the cooler hours; their seeds sprout just in time to meet the rains, then flower and fruit before the dry season.

These are signs of resilience that have mostly disappeared from domesticated food crops, which often need lots of water and nutrients, as well as protection from the elements, pests, and diseases. Re-introducing these traits into our food crops via plant breeding brings a much-needed “wildness” from crop relatives to their domesticated kin. But breeding can only happen if the wild species are still around to be able to offer their gifts.

The chiltepins and other crop wild relatives in the canyon are the fortunate ones. Their habitat has been actively protected for the last 20 years, thanks to the work of conservation groups like Native Seeds/SEARCH, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, and the University of Arizona Southwest Center, who work directly with the US Forest Service. Collaborative efforts helped establish the 2,300-acre Wild Chile Botanical Area in the Colorado National Forest.

Unfortunately, most crop wild relatives are threatened by habitat loss due to urbanization, agricultural expansion, mining, and other land use changes, or by invasive species, pollution, over-harvesting, and climate change. Despite the challenges, the wild plants adapt to the changing climate, pests, and diseases. To be safeguarded and available for crop breeding, they likewise need to be collected and conserved in seed banks, botanical gardens, and other facilities where they will be available for research and education. The United Nations recognizes the importance of conserving crop wild relatives in Target 2.5 of its goal of Zero Hunger.

AMONG THE MOST INTERESTING CROP WILD RELATIVES found in the Wild Chile Reserve is the tepary, whose cultivated cousin is among the most heat and drought tolerant crops in the world. As climate change exacerbates extreme heat and drought, teparies will likely become an increasingly important food resource, both culturally and nutritionally, for many indigenous groups in the region.

Because the tepary is such an important genetic and cultural resource, it makes sense that I find it at Native Seeds/SEARCH a non-profit seed bank co-founded by Gary Paul Nabhan back in 1983, with a goal to preserve and safeguard seeds native to the Southwest. The collection now holds 90 different species (crop types) and 1900 different seed accessions (an accession is a specific seed collected at a specific place and time). The eight accessions of wild teparies come from San Pedro River Valley, Rock Corral Canyon, Sycamore Canyon, Santa Rita Mountains, Kitt Peak, and Santa Catalina Mountains; two of them also come from areas in Mexico: Tiburon Island (Sea of Cortez), and another from Chihuahua near the Sonoran border. They also have 78 accessions of domesticated teparies in the seed bank from all over Northern Mexico and the Southwestern US.

As Sheryl Joy, Collections Curator at Native Seeds/SEARCH explains, “One of the most special things about our conservation model is that we not only safeguard seed varieties in our seed bank, but also work constantly to make these seeds available to people to grow and use. Seeds are most valuable when people grow them, save them, cook them, eat them, and enjoy them. That is how seed conservation can be ensured— when people make them a regular part of their lives.”

The decision to grow out a seed is based on several factors, including popularity and utility of the seed, the length of time since the last growout, the longevity of the seed in cold storage, and the ability of NS/Sto work with a diverse growers who are excited to grow the crops in their communities.

Because many seeds in their collection are important to the indigenous groups that stewarded them for generations, NS/S makes the seeds freely available to those communities from which the seed was collected. Though economic and social pressures have made it difficult for many of these communities to maintain their traditional foodways, seeds remain important to their cultural identity as well as their health. Another special facet of NS/S’s collection is that seeds are adapted to the hot, arid conditions of the southwest. As climate change brings desert-like conditions to more regions, crop wild relative seeds’ special adaptations will become more and more important.

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA’S DESERT LABORATORY, a 115-year-old research institute on Tumamoc Hill – an 860-acre reserve on the edge of downtown Tucson, was established to understand how native local plants survive—or even thrive— tough environments. What was perhaps not as well recognized back then was how much of the native flora provided critical sustenance to people, nor how diverse and interesting were the local wild relatives of humanity’s food crops.

Recent studies are showing that Arizona is among the US states with the richest range of culturally and economically valuable wild plants. Native species from dozens of plant genera have already been used to improve resilience to climatic stresses, enhance resistance to pests and diseases, improve nutritional quality, and offer hardier rootstock for fruit, nut, and berry crops. Moreover, dozens of native wild plants continue to provide nutrition and cultural value directly to locals. In total, over 1,000 wild species grow across Arizona, half of which are either close relatives of domesticated crops or valuable food sources in their own right. Of these, around 150 are ancestors or close cousins of globally-important crops.

With all this in mind, our diverse group had come together to facilitate effective work between seed banks, botanic gardens, wild lands managers, academics, conservation organizations, and educators to ensure the survival and continued availability of desert plants.

The good news is that more than half of the crop wild relative species found in two nearby reserves – Rock Corral and Walnut Gulch – are already safeguarded in Arizona’s seed banks, nurseries and botanical garden collections. The bad news is that much work remains to be done to ensure that other important crop wild relatives and edible desert plants are conserved.

TUCSON IS THE FIRST UNESCO DESIGNATED CITY of gastronomy in the US, and both Tucson and the Rock Corral Wild Chile Reserve are part of the new Santa Cruz Valley Natural Heritage Area. These designations were given because Tucson has become a model for desert cities around the world: they’re safeguarding and restoring both wild and cultivated food plant diversity, with over two thousand varieties freely shared through their free seed library network.

Talking about a food revolution without food at the table isn’t how things are done in the desert borderlands. James Beard award-winning chef Janos Wilder of Tucson’s Downtown Kitchen provides us with the opportunity to sample a number of different dishes featuring wild plants and desert-adapted crops native to the region and other parts of North America – including a range of crop wild relatives. These included a tepary bean spread with za’atar (a blend of locally harvested wild thyme, sumac, and sesame seeds), cholla (cactus) flower buds in a cold bean salad, wild tomatillos, wild oregano, and wild rice. And, of course, the chiltepin. There are also a range of beverages fermented from wild sotol and agaves. It wasn’t difficult to convince the crowd that these wild plants were not only useful for resilience, but also tasty.

To find and purchase tepary beans, look no further than Ramona Farms, a Native American (Akimel O’Odham) farm and business based in Sacaton, Arizona, which has been growing heirloom crops like the tepary bean (white, brown and black) for over forty years.

BY THE END OF THIS VOYAGE, our group created a stronger resolve to work together to protect these hardy plants and to make sure they are available to contribute to a more resilient food future. The climate is likely to get hotter, drier, and more erratic across most of the borderlands in the years to come. Scarce moisture will become only more precious. Local food production will be even more vulnerable to the heat and drought. It’s a very real possibility that the remaining water will go to domestic uses rather than agriculture, making locals even more dependent on importing food from greener states in the U.S. and Mexico. One thing we can all agree on is that every bit of progress we can make towards being able to grow crops adapted to hotter and drier conditions will be worth it – efforts can contribute to more stable yields, lower costs for farmers, and more overall regional food security.

In recent years, collaborative initiatives have shown that it is possible to reach beyond institutional silos to catch the wild plants falling between the cracks in organizational mandates.

With the burn of fresh chile still on their lips, this group has identified five priority areas for partnership to conserve and increase awareness about the importance of crop wild relatives:

TEPARY BEANS ARE ANNUAL LEGUMES. Wild forms still exist in North America and grow as twining or weakly trailing intermediate vines that climb shrubs or trees. The domesticated varieties are bushier and grow up to one foot tall and 20 inches in diameter. The leaves are trifoliate and have narrow, pointed leaflets. The flowers vary from white to light colored. The fruits grow in small pods, from 1.25 to 3 inches long, and contain 2 to 7 seeds. Domesticated beans are ⅓ of an inch long and can vary in color from brown to beige to black to white, whereas wild seeds are smaller, dark, and mottled. Tepary bean roots are associated with nitrogen fixing bacteria (USDA).

There are two major types of tepary beans: white tepary beans and brown tepary beans. The two varieties have similar uses, but white tepary beans are sweeter than the more earthy tepary beans. Although tepary beans can be ground into meal, like most common beans, they are most prepared as a whole, dried shell (USDA). Drying the beans is beneficial because it increases shelf life. Prior to cooking the beans, they should be soaked (preferably overnight) as soaking greatly decreases cooking time. To prepare the beans, boil them for several hours or until tender (Ramona Farms). Once cooked, the beans can be used in salads, stews, chilis, and other classic bean dishes. However, it must be noted that tepary beans are toxic when raw, so it is crucial to ensure the beans are tender before consuming them (NUS).

Tepary beans are a more nutritious alternative to more common beans, like pinto and navy beans. They are high in protein and dietary fiber, nutrients which combat diabetes (Native Seeds). Further, tepary beans contain lysine, an essential amino acid that aids in protein development and lowers cholesterol. Tepary beans are also iron-rich, and have the potential to combat widespread iron deficiency – up to 30% of the world is iron deficient (Bhardwaj and Hamama). High levels of unsaturated fats in legumes like tepary beans also reduce the risk of colon and breast cancer and cardiovascular disease (Jiri and Mafongoya).

Traditionally, tepary beans are grown at the start of the heavy rain season (mid-June to mid-July). They can be grown using modern irrigation techniques, but excessive irrigation or rainfall will lead to poor establishment and can cause more vegetative growth rather than high seed production. Soil tests should be done before planting to know if any nutrient amendments are necessary, but nitrogen fertilizers should be limited so as to not inhibit root nodulation and nitrogen fixation. The first harvest can be from 60-120 days after planting. The beans can be harvested by hand or mechanically. Tepary bean is at risk of common bean diseases like common mosaic virus (USDA).

Tepary beans originated in North America and have been cultivated for thousands of years. Although their archeological record does not show their first domestication’s exact location, one record discovered domesticated tepary beans in the Tehuacán Valley, Mexico dating back approximately 2500 years. In Arizona, the beans were found in Hohokam sites dating back around 1000 years. The Tohono O’odham tribe in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona has one of the strongest cultural ties to tepary bean cultivation. One of the group’s myths teaches that white tepary beans were scattered across the sky to form the Milky Way. Teparies were widely grown in the Tohono O’odham Nation until World War II, when many farmers joined the military or began working on large-scale cotton farms. The Tohono O’odham people are now working to incorporate the tepary bean, among other traditional foods, back into their diet including in school lunches (USDA).

After recognizing tepary beans’ capacity to fight malnutrition and food insecurity, Bioversity International launched a series of surveys in Guatemala with hopes of integrating tepary beans into the common bean value chain. Stakeholders, like manufacturers and distributors, in Guatemala’s bean value chain showed interest in tepary beans. Further, food industry actors stated that they were willing to undergo trials to determine whether value added tepary bean products can meet industry quality and nutritional standards (Bioversity International). Existing research affirms tepary beans’ nutritional profile and high resistance to drought, but in order to determine if tepary beans can serve as an alternative to common beans, additional, locally-driven research must be conducted.

About

Lexicon of Food is produced by The Lexicon, an international NGO that brings together food companies, government agencies, financial institutions, scientists, entrepreneurs, and food producers from across the globe to tackle some of the most complex challenges facing our food systems.

Team

The Agrobiodiversity Channel was developed by an invitation-only food systems solutions activator created by The Lexicon with support from Food at Google. The activator model fosters unprecedented collaborations between leading food service companies, environmental NGOs, government agencies, and technical experts from across the globe.

This website was built by The Lexicon™, a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit organization headquartered in Petaluma, CA.

Check out our Privacy Policy, Cookie Policy, and Terms of Use.

© 2024 – Lexicon of Food™

Professionals at universities and research institutions seeking scholarly articles, data, and resources.

Tools to align investment and grant making strategies with advances in agriculture, food production, and emerging markets.

Professionals seeking information on ingredient sourcing, menu planning, sustainability, and industry trends.

Chefs and food industry professionals seeking inspiration on ingredients and sustainable trends to enhance their work.

Individuals interested in food products, recipes, nutrition, and health-related information for personal or family use.

Individuals producing food, fiber, feed, and other agricultural products that support both local and global food systems.

This online platform is years in the making, featuring the contributions of 1000+ companies and NGOs across a dzen domain areas. To introduce you to their work, we’ve assembled personalized experiences with insights from our community of international experts.

Businesses engaged in food production, processing, and distribution that seek insight from domain experts

Those offering specialized resources and support and guidance in agriculture, food production, and nutrition.

Individuals who engage and educate audience on themes related to agriculture, food production, and nutrition.

Nutritional information for professionals offering informed dietary choices that help others reach their health objectives

Those advocating for greater awareness and stronger action to address climate impacts on agriculture and food security.

Professionals seeking curriculum materials, lesson plans, and learning tools related to food and agriculture.

We have no idea who grows our food, what farming practices they use, the communities they support, or what processing it undergoes before reaching our plates.

As a result, we have no ability to make food purchases that align with our values as individuals, or our missions as companies.

To change that, we’ve asked experts to demystify the complexity of food purchasing so that you can better informed decisions about what you buy.

The Lexicon of Food’s community of experts share their insights and experiences on the complex journey food takes to reach our plates. Their work underscores the need for greater transparency and better informed decision-making in shaping a healthier and more sustainable food system for all.

Over half the world’s agricultural production comes from only three crops. Can we bring greater diversity to our plates?

In the US, four companies control nearly 85% of the beef we consume. Can we develop more regionally-based markets?

How can we develop alternatives to single-use plastics that are more sustainable and environmentally friendly?

Could changing the way we grow our food provide benefits for people and the planet, and even respond to climate change?

Can we meet the growing global demand for protein while reducing our reliance on traditional animal agriculture?

It’s not only important what we eat but what our food comes in. Can we develop tools that identify toxic materials used in food packaging?

Explore The Lexicon’s collection of immersive storytelling experiences featuring insights from our community of international experts.

The Great Protein Shift

Our experts use an engaging interactive approach to break down the technologies used to create these novel proteins.

Ten Principles for Regenerative Agriculture

What is regenerative agriculture? We’ve developed a framework to explain the principles, practices, ecological benefits and language of regenerative agriculture, then connected them to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Food-related chronic diseases are the biggest burden on healthcare systems. What would happen if we treated food as medicine?

How can we responsibly manage our ocean fisheries so there’s enough seafood for everyone now and for generations to come?

Mobilizing agronomists, farmers, NGOs, chefs, and food companies in defense of biodiversity in nature, agriculture, and on our plates.

Can governments develop guidelines that shift consumer diets, promote balanced nutrition and reduce the risk of chronic disease?

Will sustainably raising shellfish, finfish, shrimp and algae meet the growing demand for seafood while reducing pressure on wild fisheries?

How can a universal visual language to describe our food systems bridge cultural barriers and increase consumer literacy?

What if making the right food choices could be an effective tool for addressing a range of global challenges?

Let’s start with climate change. While it presents our planet with existential challenges, biodiversity loss, desertification, and water scarcity should be of equal concern—they’re all connected.

Instead of seeking singular solutions, we must develop a holistic approach, one that channel our collective energies and achieve positive impacts where they matter most.

To maximize our collective impact, EBF can help consumers focus on six equally important ecological benefits: air, water, soil, biodiversity, equity, and carbon.

We’ve gathered domain experts from over 1,000 companies and organizations working at the intersection of food, agriculture, conservation, and climate change.

The Lexicon™ is a California-based nonprofit founded in 2009 with a focus on positive solutions for a more sustainable planet.

For the past five years, it has developed an “activator for good ideas” with support from Food at Google. This model gathers domain experts from over 1,000 companies and organizations working at the intersection of food, agriculture, conservation, and climate change.

Together, the community has reached consensus on strategies that respond to challenges across multiple domain areas, including biodiversity, regenerative agriculture, food packaging, aquaculture, and the missing middle in supply chains for meat.

Lexicon of Food is the first public release of that work.

Over half the world’s agricultural production comes from only three crops. Can we bring greater diversity to our plates?

In the US, four companies control nearly 85% of the beef we consume. Can we develop more regionally-based markets?

How can we develop alternatives to single-use plastics that are more sustainable and environmentally friendly?

Could changing the way we grow our food provide benefits for people and the planet, and even respond to climate change?

Can we meet the growing global demand for protein while reducing our reliance on traditional animal agriculture?

It’s not only important what we eat but what our food comes in. Can we develop tools that identify toxic materials used in food packaging?

Explore The Lexicon’s collection of immersive storytelling experiences featuring insights from our community of international experts.

The Great Protein Shift

Our experts use an engaging interactive approach to break down the technologies used to create these novel proteins.

Ten Principles for Regenerative Agriculture

What is regenerative agriculture? We’ve developed a framework to explain the principles, practices, ecological benefits and language of regenerative agriculture, then connected them to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Food-related chronic diseases are the biggest burden on healthcare systems. What would happen if we treated food as medicine?

How can we responsibly manage our ocean fisheries so there’s enough seafood for everyone now and for generations to come?

Mobilizing agronomists, farmers, NGOs, chefs, and food companies in defense of biodiversity in nature, agriculture, and on our plates.

Can governments develop guidelines that shift consumer diets, promote balanced nutrition and reduce the risk of chronic disease?

Will sustainably raising shellfish, finfish, shrimp and algae meet the growing demand for seafood while reducing pressure on wild fisheries?

How can a universal visual language to describe our food systems bridge cultural barriers and increase consumer literacy?

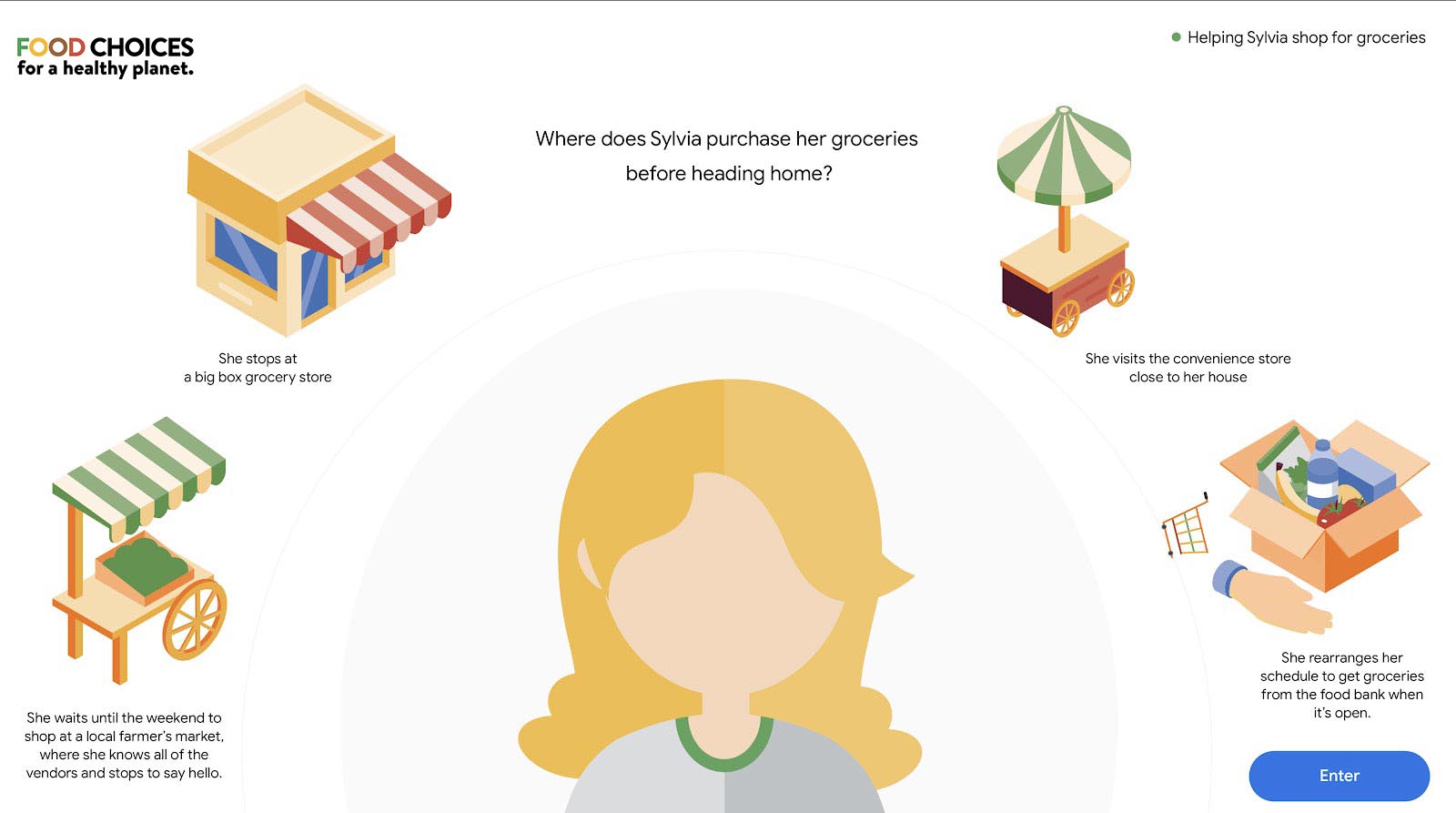

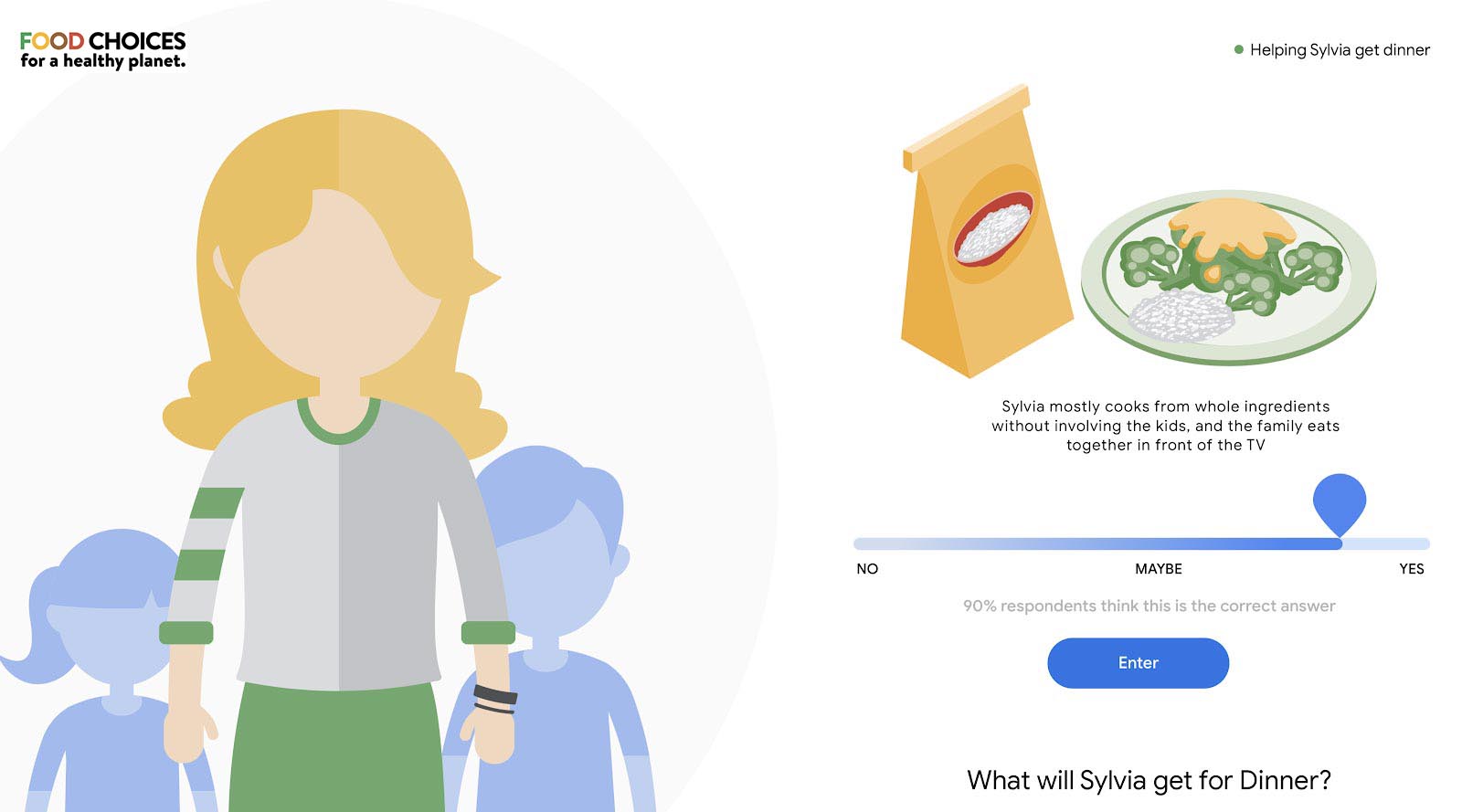

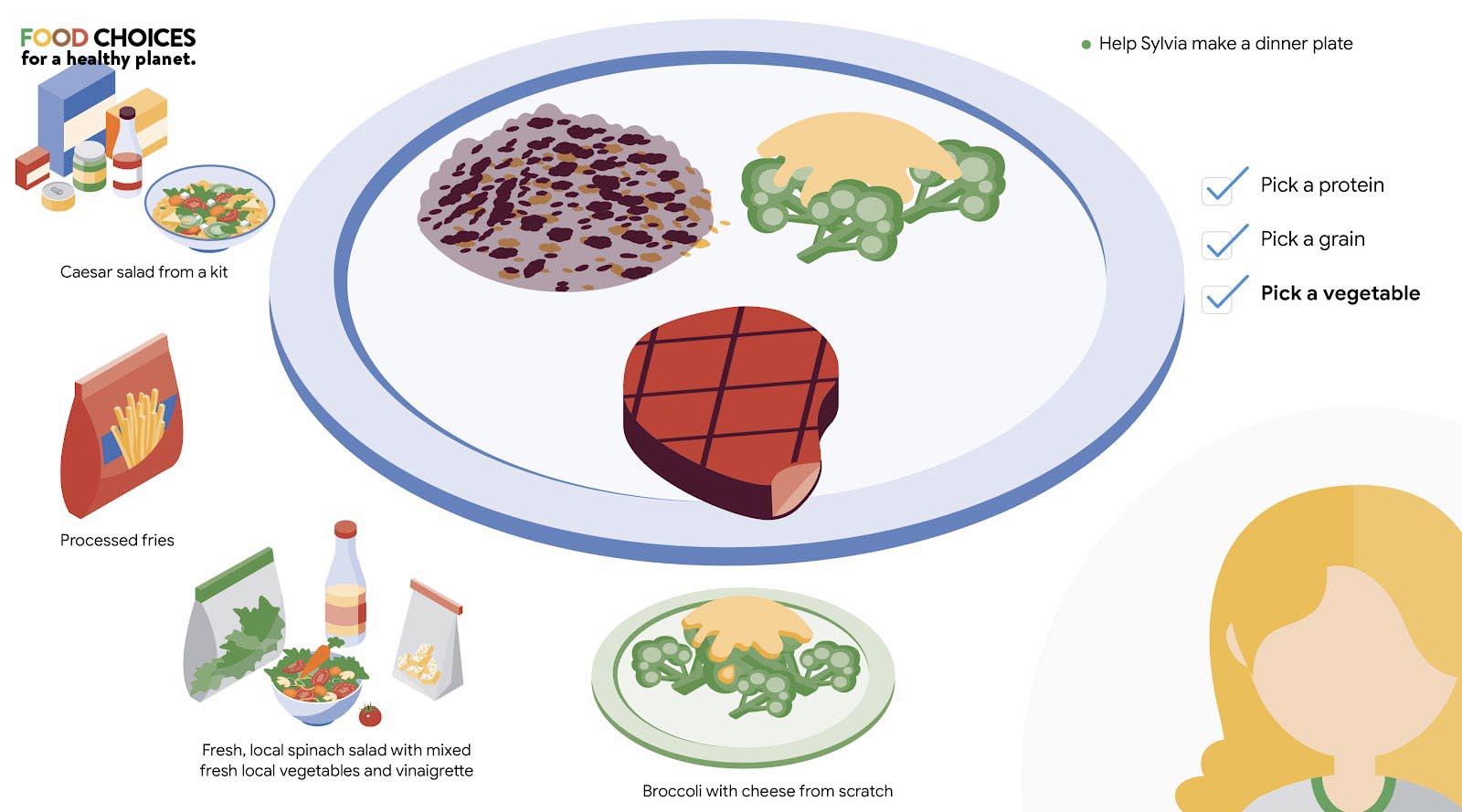

This game was designed to raise awareness about the impacts our food choices have on our own health, but also the environment, climate change and the cultures in which we live.

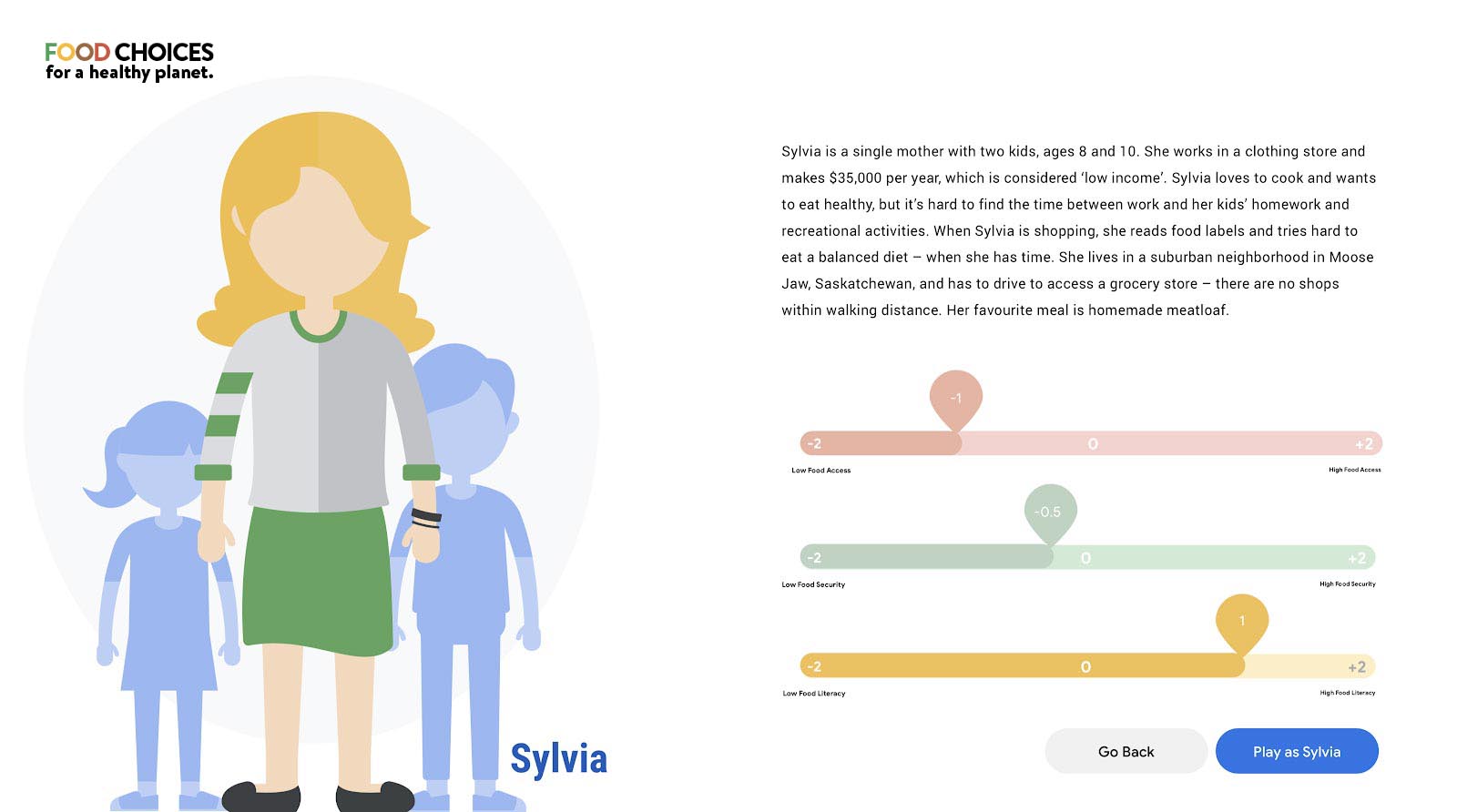

First, you can choose one of the four global regions and pick a character that you want to play.

Each region has distinct cultural, economic, historical, and agricultural capacities to feed itself, and each character faces different challenges, such as varied access to food, higher or lower family income, and food literacy.

As you take your character through their day, select the choices you think they might make given their situation.

At the end of the day you will get a report on the impact of your food choices on five areas: health, healthcare, climate, environment and culture. Take some time to read through them. Now go back and try again. Can you make improvements in all five areas? Did one area score higher, but another score lower?

FOOD CHOICES FOR A HEALTHY PLANET will help you better understand how all these regions and characters’ particularities can influence our food choices, and how our food choices can impact our personal health, national healthcare, environment, climate, and culture. Let’s Play!

The FOOD CHOICES FOR A HEALTHY PLANET game allows users to experience the dramatic connections between food and climate in a unique and engaging way. The venue and the game set-up provides attendees with a fun experience, with a potential to add a new layer of storytelling about this topic.

Starting the game: the pilot version of the game features four country/regions: Each reflects a different way people (and the national dietary guidelines) look at diets: Nordic Countries (sustainability), Brazil (local and whole foods instead of ultra-processed foods); Canada (plant-forward), and Indonesia (developing countries).

Personalizing the game: players begin by choosing a country and then a character who they help in making food choices over the course of one day. Later versions may allow for creating custom avatars.

Making tough food choices: This interactive game for all ages shows how the food choices we make impact our health and the environment, and even contribute to climate change.

What we eat matters: at the end of each game, players learn that every decision they make impacts not only their health, but a national healthcare system, the environment, climate and even culture.

We’d love to know more about you and why you think you will be a great fit for this position! Shoot us an email introducing you and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible!

Providing best water quality conditions to ensure optimal living condition for growth, breeding and other physiological needs

Water quality is sourced from natural seawater with dependency on the tidal system. Water is treated to adjust pH and alkalinity before stocking.

Producers that own and manages the farm operating under small-scale farming model with limited input, investment which leads to low to medium production yield

All 1,149 of our farmers in both regencies are smallholder farmers who operate with low stocking density, traditional ponds, and no use of any other intensification technology.

Safe working conditions — cleanliness, lighting, equipment, paid overtime, hazard safety, etc. — happen when businesses conduct workplace safety audits and invest in the wellbeing of their employees

Company ensure implementation of safe working conditions by applying representative of workers to health and safety and conduct regular health and safety training. The practices are proven by ASIC standards’ implementation

Implementation of farming operations, management and trading that impact positively to community wellbeing and sustainable better way of living

The company works with local stakeholders and local governments to create support for farmers and the farming community in increasing resilience. Our farming community is empowered by local stakeholders continuously to maintain a long generation of farmers.

Freezing seafood rapidly when it is at peak freshness to ensure a higher quality and longer lasting product

Our harvests are immediately frozen with ice flakes in layers in cool boxes. Boxes are equipped with paper records and coding for traceability. We ensure that our harvests are processed with the utmost care at <-18 degrees Celsius.

Sourcing plant based ingredients, like soy, from producers that do not destroy forests to increase their growing area and produce fish feed ingredients

With adjacent locations to mangroves and coastal areas, our farmers and company are committed to no deforestation at any scale. Mangrove rehabilitation and replantation are conducted every year in collaboration with local authorities. Our farms are not established in protected habitats and have not resulted from deforestation activity since the beginning of our establishment.

Implement only natural feeds grown in water for aquatic animal’s feed without use of commercial feed

Our black tiger shrimps are not fed using commercial feed. The system is zero input and depends fully on natural feed grown in the pond. Our farmers use organic fertilizer and probiotics to enhance the water quality.

Enhance biodiversity through integration of nature conservation and food production without negative impact to surrounding ecosysytem

As our practices are natural, organic, and zero input, farms coexist with surrounding biodiversity which increases the volume of polyculture and mangrove coverage area. Farmers’ groups, along with the company, conduct regular benthic assessments, river cleaning, and mangrove planting.

THE TERM “MOONSHOT” IS OFTEN USED TO DESCRIBE an initiative that goes beyond the confines of the present by transforming our greatest aspirations into reality, but the story of a moonshot isn’t that of a single rocket. In fact, the Apollo program that put Neil Armstrong on the moon was actually preceded by the Gemini program, which in a two-year span rapidly put ten rockets into space. This “accelerated” process — with a new mission nearly every 2-3 months — allowed NASA to rapidly iterate, validate their findings and learn from their mistakes. Telemetry. Propulsion. Re-entry. Each mission helped NASA build and test a new piece of the puzzle.

The program also had its fair share of creative challenges, especially at the outset, as the urgency of the task at hand required that the roadmap for getting to the moon be written in parallel with the rapid pace of Gemini missions. Through it all, the NASA teams never lost sight of their ultimate goal, and the teams finally aligned on their shared responsibilities. Within three years of Gemini’s conclusion, a man did walk on the moon.

FACT is a food systems solutions activator that assesses the current food landscape, engages with key influencers, identifies trends, surveys innovative work and creates greater visibility for ideas and practices with the potential to shift key food and agricultural paradigms.

Each activator focuses on a single moonshot; instead of producing white papers, policy briefs or peer-reviewed articles, these teams design and implement blueprints for action. At the end of each activator, their work is released to the public and open-sourced.

As with any rapid iteration process, many of our activators re-assess their initial plans and pivot to address new challenges along the way. Still, one thing has remained constant: their conviction that by working together and pooling their knowledge and resources, they can create a multiplier effect to more rapidly activate change.

Co-Founder

THE LEXICON

Vice President

Global Workplace Programs

GOOGLE

Who can enter and how selections are made.

A Greener Blue is a global call to action that is open to individuals and teams from all over the world. Below is a non-exhaustive list of subjects the initiative targets.

To apply, prospective participants will need to fill out the form on the website, by filling out each part of it. Applications left incomplete or containing information that is not complete enough will receive a low score and have less chance of being admitted to the storytelling lab.

Nonprofit organizations, communities of fishers and fish farmers and companies that are seeking a closer partnership or special support can also apply by contacting hello@thelexicon.org and interacting with the members of our team.

Special attention will be given to the section of the form regarding the stories that the applicants want to tell and the reasons for participating. All proposals for stories regarding small-scale or artisanal fishers or aquaculturists, communities of artisanal fishers or aquaculturists, and workers in different steps of the seafood value chain will be considered.

Stories should show the important role that these figures play in building a more sustainable seafood system. To help with this narrative, the initiative has identified 10 principles that define a more sustainable seafood system. These can be viewed on the initiative’s website and they state:

Seafood is sustainable when:

Proposed stories should show one or more of these principles in practice.

Applications are open from the 28th of June to the 15th of August 2022. There will be 50 selected applicants who will be granted access to The Lexicon’s Total Storytelling Lab. These 50 applicants will be asked to accept and sign a learning agreement and acceptance of participation document with which they agree to respect The Lexicon’s code of conduct.

The first part of the lab will take place online between August the 22nd and August the 26th and focus on training participants on the foundation of storytelling, supporting them to create a production plan, and aligning all of them around a shared vision.

Based on their motivation, quality of the story, geography, and participation in the online Lab, a selected group of participants will be gifted a GoPro camera offered to the program by GoPro For A Change. Participants who are selected to receive the GoPro camera will need to sign an acceptance and usage agreement.

The second part of the Storytelling Lab will consist of a production period in which each participant will be supported in the production of their own story. This period goes from August 26th to October 13th. Each participant will have the opportunity to access special mentorship from an international network of storytellers and seafood experts who will help them build their story. The Lexicon also provides editors, animators, and graphic designers to support participants with more technical skills.

The final deadline to submit the stories is the 14th of October. Participants will be able to both submit complete edited stories, or footage accompanied by a storyboard to be assembled by The Lexicon’s team.

All applicants who will exhibit conduct and behavior that is contrary to The Lexicon’s code of conduct will be automatically disqualified. This includes applicants proposing stories that openly discriminate against a social or ethnic group, advocate for a political group, incite violence against any group, or incite to commit crimes of any kind.

All submissions must be the entrant’s original work. Submissions must not infringe upon the trademark, copyright, moral rights, intellectual rights, or rights of privacy of any entity or person.

Participants will retain the copyrights to their work while also granting access to The Lexicon and the other partners of the initiative to share their contributions as part of A Greener Blue Global Storytelling Initiative.

If a potential selected applicant cannot be reached by the team of the Initiative within three (3) working days, using the contact information provided at the time of entry, or if the communication is returned as undeliverable, that potential participant shall forfeit.

Selected applicants will be granted access to an advanced Storytelling Lab taught and facilitated by Douglas Gayeton, award-winning storyteller and information architect, co-founder of The Lexicon. In this course, participants will learn new techniques that will improve their storytelling skills and be able to better communicate their work with a global audience. This skill includes (but is not limited to) how to build a production plan for a documentary, how to find and interact with subjects, and how to shoot a short documentary.

Twenty of the participants will receive a GoPro Hero 11 Digital Video and Audio Cameras by September 15, 2022. Additional participants may receive GoPro Digital Video and Audio Cameras to be announced at a later date. The recipients will be selected by advisors to the program and will be based on selection criteria (see below) on proposals by Storytelling Lab participants. The selections will keep in accordance with Lab criteria concerning geography, active participation in the Storytelling Lab and commitment to the creation of a story for the Initiative, a GoPro Camera to use to complete the storytelling lab and document their story. These recipients will be asked to sign an acceptance letter with terms of use and condition to receive the camera.

The Lexicon provides video editors, graphic designers, and animators to support the participants to complete their stories.

The submitted stories will be showcased during international and local events, starting from the closing event of the International Year of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022 in Rome, in January 2023. The authors of the stories will be credited and may be invited to join.

Storytelling lab participation:

Applicants that will be granted access to the storytelling Lab will be evaluated based on the entries they provided in the online form, and in particular:

Applications will be evaluated by a team of 4 judges from The Lexicon, GSSI and the team of IYAFA (Selection committee).

When selecting applications, the call promoters may request additional documentation or interviews both for the purpose of verifying compliance with eligibility requirements and to facilitate proposal evaluation.

Camera recipients:

Participants to the Storytelling Lab who will be given a GoPro camera will be selected based on:

The evaluation will be carried out by a team of 4 judges from The Lexicon, GSSI and the team of IYAFA (Selection committee).

Incidental expenses and all other costs and expenses which are not specifically listed in these Official Rules but which may be associated with the acceptance, receipt and use of the Storytelling Lab and the camera are solely the responsibility of the respective participants and are not covered by The Lexicon or any of the A Greener Blue partners.

All participants who receive a Camera are required to sign an agreement allowing GoPro for a Cause, The Lexicon and GSSI to utilize the films for A Greener Blue and their promotional purposes. All participants will be required to an agreement to upload their footage into the shared drive of The Lexicon and make the stories, films and images available for The Lexicon and the promoting partners of A Greener Blue.